The church has long understood the

Bible to be the unique and authoritative source for knowing God through the

power of the Holy Spirit, and for understanding God’s plan for his people. The story of God speaking and communicating

with his people is not a new phenomenon.

Scripture itself testifies to God’s desire to reveal himself, and so his

will to his people, through his Word.

The

Reformed tradition, through its confessions, has a long history of upholding

and adhering to this understanding of the nature of Scripture—usually referred

to as Sola Scriptura. Sola Scriptura was

not a new teaching at the time of the Reformation; rather, it was one that had

been reclaimed from the past. It

was Irenaeus of Lyon who stated that while the Apostles at first preached

orally, their teaching was later committed to writing (the Scriptures), and the

Scriptures had since that day become the pillar and ground of the Church’s

faith. He wrote, “We have learned from none other the plan of our salvation,

than from those through whom the gospel has come down to us, which they did at

one time proclaim in public, and, at a later period, by the will of God, handed

down to us in the Scriptures, to be the ground and pillar of our faith.” [1]

|

| Ireneaus of Lyon |

The Gnostics may have been the

very first group to suggest and teach that they possessed an Apostolic oral tradition

that was independent from Scripture. Irenaeus

and Tertullian rejected such a notion and appealed to Scripture alone for the

proclamation and defense of doctrine. Church historian, Ellen Flessman-van Leer

affirms this fact,

For Tertullian, Scripture

is the only means for refuting or validating a doctrine

regarding its content… For Irenaeus, the Church doctrine is certainly never

purely traditional; on the contrary, the thought that there could be some

truth, transmitted exclusively viva voce (orally), is a Gnostic line of

thought… If Irenaeus wants to prove the truth of a doctrine materially, he

turns to Scripture, because therein the teaching of the apostles is objectively

accessible. Proof from tradition and Scripture serve one and the same end: to

identify the teaching of the Church as the original apostolic teaching. The

first establishes that the teaching of the Church is this apostolic teaching,

and the second, what this apostolic teaching is.[2]

The Bible was the ultimate

authority for the Early Church. It was materially sufficient, and the final

arbiter in all matters of doctrinal truth. As J.N.D. Kelly has pointed out,

The clearest token of the prestige enjoyed by Scripture

is the fact that almost the entire theological effort of the Fathers, whether

their aims were polemical or constructive, was expended upon what amounted to

the exposition of the Bible. Further, it

was everywhere taken for granted that, for any doctrine to win acceptance, it

had first to establish its Scriptural basis.[3]

Another example of the early church’s

faithfulness to the principle of Sola Scriptura is clearly seen in the writings

of Cyril of Jerusalem. He is the author of what is known as the Catechetical

Lectures. This work is an extensive series of lectures given to new believers (catechumens)

instructing them concerning the principle doctrines of the faith. It is a

complete explanation of the faith of the church of his day. His teaching is

thoroughly grounded in Scripture.

He states in explicit terms that if he were to

present any teaching to these catechumens which could not be validated from

Scripture, they were to reject it. This fact confirms that his authority as a bishop

was subject to his conformity to the written Scriptures in his teaching.

The following excerpts are some of his statements on the final authority of

Scripture from these lectures.

This seal have thou ever on thy mind; which now by way

of summary has been touched on in its heads, and if the Lord grant, shall

hereafter be set forth according to our power, with Scripture proofs. For concerning the divine and sacred

Mysteries of the Faith, we ought not to deliver even the most casual remark

without the Holy Scriptures: nor be drawn aside by mere probabilities

and the artifices of argument. Do not then believe me because I tell thee these

things, unless thou receive from the Holy Scriptures the proof of what is set

forth: for this salvation, which is of our faith, is not by ingenious

reasonings, but by proof from the Holy Scriptures….But take thou and hold that

faith only as a learner and in profession, which is by the Church delivered to thee, and is established from all Scripture. For since all

cannot read the Scripture, but some as being unlearned, others by business, are

hindered from the knowledge of them; in order that the soul may not perish for

lack of instruction, in the Articles which are few we comprehend the whole

doctrine of Faith…And for the present, commit to memory the Faith, merely

listening to the words; and expect at the fitting season the proof of each of

its parts from the Divine Scriptures. For the Articles of the Faith were not

composed at the good pleasure of men: but the most important points chosen from

all Scriptures, make up the one teaching of the Faith. And, as the mustard seed in a little grain contains many branches, thus also

this Faith, in a few words, hath enfolded in its bosom the whole knowledge of

godliness contained both in the Old and New Testaments. Behold, therefore,

brethren and hold the traditions which ye now receive, and write them on the

table of your hearts.”[4]

Gregory of Nyssa shared this

understanding with Cyril of Jerusalem (and so Ireneaus and Tertullian) when he

wrote,

The generality of men still fluctuate in their opinions

about this, which are as erroneous as they are numerous. As for ourselves, if

the Gentile philosophy, which deals methodically with all these points, were

really adequate for a demonstration, it would certainly be superfluous to add a

discussion on the soul to those speculations. But while the latter proceeded,

on the subject of the soul, as far in the direction of supposed consequences as

the thinker pleased, we are not entitled to such license, I mean that of

affirming what we please; we make the

Holy Scriptures the rule and the measure of every tenet; we necessarily

fix our eyes upon that, and approve that alone which may be made to harmonize with

the intention of those writings.[5]

Augustine of Hippo thought so

highly of Scripture that he wrote an entire book on how to properly study it

titled Teaching Christianity (De Doctrina

Christiana)!

In 1556 Heinrich Bullinger, one of the original co-authors

of the First Helvetic Confession, penned the Second Helvetic Confession. The opening

lines of the Second Helvetic Confession begin,

We believe and confess the canonical Scriptures of the

holy prophets and apostles of both Testaments to be the true Word of God, and

to have sufficient authority of themselves, not of men. For God himself spoke to the fathers,

prophets, apostles, and still speaks to us through the Holy Scriptures.[6]

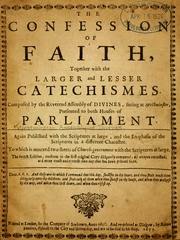

The

Westminster Standards, that bastion of Presbyterian confessionalism (full disclosure: I am

ordained in a denomination that requires subscription to Westminster), has much

to teach regarding the Word of God. The Shorter Catechism, Question 2 asks,

“What rule hath God given to direct us how we may glorify and enjoy him?” The answer, “The Word of God which is

contained in the Scriptures of the Old and New Testaments is the only rule to

direct us how we may glorify and enjoy him.” The Westminster Larger Catechism

Question 3 asks, “What is the Word of God?”

The answer, “The holy Scriptures of the Old and New Testaments are the

Word of God, the only rule of faith and obedience.” Question 4 of the WLC asks,

“How doth it appear that the Scriptures are the Word of God?” The answer,

The Scriptures manifest themselves to be the Word of

God, by their majesty and purity; by the consent of all the parts, and the

scope of the whole, which is to give all glory to God; by their light and power

to convince and convert sinners, to comfort and build up believers unto

salvation. But the Spirit of God,

bearing witness by and with the Scriptures in the heart of man, is alone able

fully to persuade it that they are the very Word of God.

The

Westminster Confession of Faith clearly articulates the authority of God’s Word

when we read, “The authority of Holy Scripture, for which it ought to be

believed and obeyed, dependeth not upon the testimony of any man or church, but

wholly upon God (who is truth itself), the author thereof; and therefore it is

to be received, because it is the Word of God.”[7]

Reformation/Reformed confessions and catechisms could be

quoted from endlessly to support the claim that Christians should find God’s

revelation for them in the Bible, but rather than drone on endlessly with

confessional references, let us look to the Scriptures themselves. The Biblical

and theological foundations could take up several volumes of work as the

references are exceedingly numerous. In

the next chapter we will look at a number of Scriptures to help us better

understand the utter importance of relying on God’s Word foremost in

understanding the Truth of God.

Spiritual disciplines such as fasting, solitude, meditation,

study, simplicity, submission, service, confession, worship, guidance, and

celebration are all useful and wonderful tools in making us more aware of the

presence of God in our lives. Unless they are rooted in the Word of God, though,

they are mostly empty exercises. B.M.

Fanning writes, “Foundational to biblical theology and religion is the

conviction that God has spoken. Through

his word, God has revealed himself, his will and his actions on behalf of his

people and the world.”[8] He

continues later in the article,

Through his word God

reveals what he is like, what he has done and will do in the outworking of his

purposes, and how humankind should respond to him…Through the word God reaches

out to his people and expresses his emotions towards them, and through the word

his people are enabled to know him more fully.

The word of the Lord is thus an extension of his grace and power towards

the people he had chosen and through them towards the nations of the world.[9]

John Calvin adds,

The Scriptures attain

full authority among believers only when men regard them as having sprung from

heaven, as if there the living words of God were heard…It is utterly vain,

then, to pretend that the power of judging Scripture so lies with the church

that its certainty depends upon churchly assent. Thus, while the church receives and gives its

seal of approval to the Scriptures, it does not thereby render authentic what

is otherwise doubtful or controversial.[10]

John Leith, long time professor of theology at Union

Theological Seminary in Richmond, Virginia, offers up support for Calvin’s

position,

|

| Dr. John H. Leith |

The Holy Scriptures are

both a means of grace and the norm of the church’s life. The Bible is the church’s memory, inspired by

the Holy Spirit, of those events that are the foundation of the Christian life

in history. It is the church’s witness

to the gospel and the content of its preaching…The Bible is the original

witness to and interpretation of God’s revelation and work “for us men and for

our salvation” in Jesus Christ. In this

sense the Bible is the church’s memory reduced to writing by the prophets and

the apostles who were the original witnesses of and believers in God’s

revelation and work that constituted his people. More specifically, the Bible is the

forward-and backward-looking testimony to Jesus Christ and as such sets the

boundaries and is the unique authorization for Christian theology and life.[11]

[1]

Roberts, Alexander and Donaldson, James, editors, Ante-Nicene Fathers

(Peabody: Hendriksen, 1995) Vol. 1, Irenaeus, “Against Heresies” 3.1.1, 414.

[2]

Flessman-van

Leer, Ellen Tradition and Scripture in the Early Church (Assen: Van

Gorcum, 1953), 184, 133, 144.

[3]

Kelly, J.N.D. Early Christian Doctrines (San Francisco: Harper

& Row, 1978), 42, 46.

[4]

A Library of the Fathers of the Holy Catholic Church (Oxford: Parker, 1845), "The Catechetical Lectures of S.

Cyril" Lecture 4.17 and Lecture 5.12.

[5]

Schaff, Phillip and Wace, Henry, editors, Nicene and Post-Nicene

Fathers (Peabody: Hendriksen, 1995) Second Series: Volume V, Gregory of

Nyssa: Dogmatic Treatises, "On the Soul and the Resurrection", 439.

[6]

“The Second Helvetic Confession” from the Book of Confessions: The Constitution of the

Presbyterian Church (USA), Part 1(Louisville: Office of the General

Assembly, 2004), 53.

[7]

These quotations from the Westminster Standards

were quoted from Book of Confessions: The

Constitution of the Presbyterian Church (USA), Part 1(Louisville: Office of

the General Assembly, 2004).

[8]

Fanning, B.M. “Word” in New Dictionary of

Biblical Theology ed. Desmond, T., Rosner, Brian S., Carson, D.A., Goldsworthy,

Graeme (Downers Grove: IVP, 2000), 848.

[9]

Ibid., 849.

[10]

Calvin, John Institutes

of the Christian Religion, ed. John T.McNeill (Louisville: John Knox Press,

1960), 1.7.1, 3.

[11]

Leith, John H. Basic Christian Doctrine (Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 1993),

270.

No comments:

Post a Comment